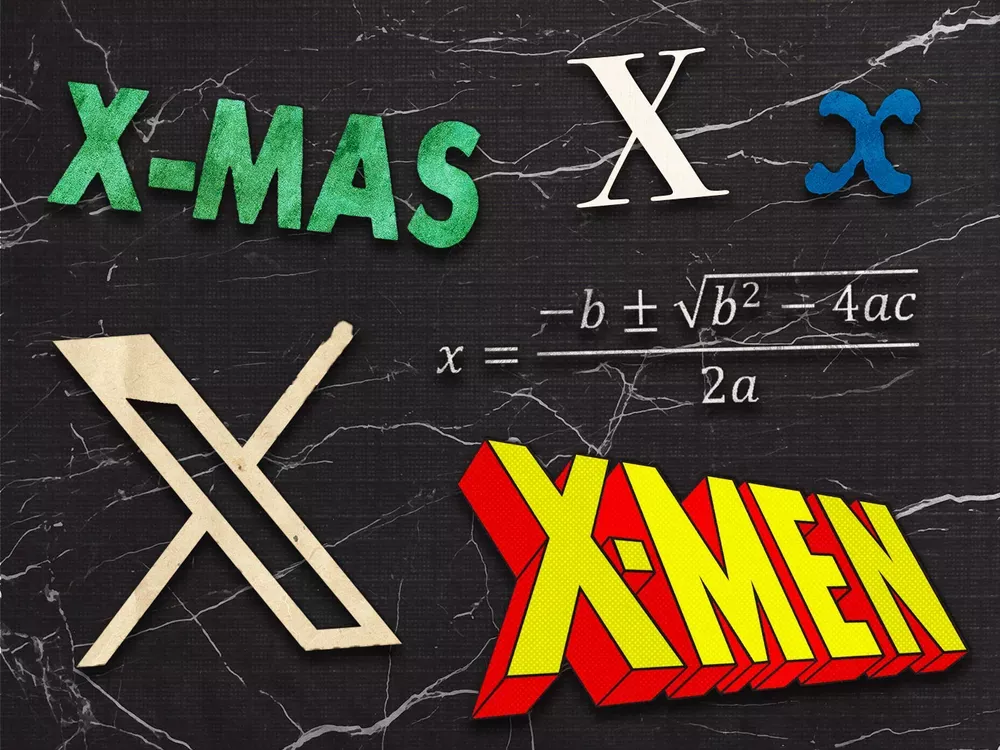

A Brief History of the Letter ‘X,’ From Algebra to X-Mas to Elon Musk

A math historian explores how “x” came to stand in for an unknown quantity

published : 16 February 2024

Even though “x” is one of the least-used letters in the English alphabet, it appears throughout American culture, from Stan Lee’s X-Men superheroes to the television series “The X-Files.” The letter “x” often symbolizes something unknown, with an air of mystery that can be appealing. Just look at Elon Musk with SpaceX, Tesla’s Model X and now X as the new name of Twitter.

You might be most familiar with “x” from math class. Many algebra problems use “x” as a variable to stand in for an unknown quantity. But why is “x” the letter chosen for this role? When and where did this convention begin?

Math enthusiasts have proposed a few different explanations, with some citing translation and others pointing to a more typographic origin. Each theory has some merit, but historians of mathematics (like me) know it’s difficult to say for sure how “x” got its role in modern algebra.

Ancient unknowns

Today, algebra is a branch of math in which abstract symbols are manipulated, using arithmetic, to solve different kinds of equations. But many ancient societies had well-developed mathematical systems and knowledge with no symbolic notation.

All ancient algebra was rhetorical. Mathematical problems and solutions were completely written out in words as part of a little story, much like the word problems you might see today in elementary school.

Ancient Egyptian mathematicians, who are perhaps best known for their geometric advances, were skilled in solving simple algebraic problems. In the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, the scribe Ahmes uses the hieroglyphics referred to as “aha” to denote the unknown quantity in his algebraic problems. For example, problem 24 asks for the value of aha if aha plus one-seventh of aha equals 19. “Aha” means something like “mass” or “heap.”

The ancient Babylonians of Mesopotamia used many different words for unknowns in their algebraic system—typically words meaning length, width, area or volume, even if the problem itself wasn’t geometric in nature. One ancient problem involved two unknowns termed the “first silver thing” and the “second silver thing.”

Mathematical know-how developed somewhat independently in many lands and in many languages. Limitations in communication prevented any immediate standardization of notation. But over time, some abbreviations crept in.

In a transitional syncopated phase, authors used some symbolic notation, but algebraic ideas were still presented mainly rhetorically. Diophantus of Alexandria used a syncopated algebra in his great work Arithmetica. He called the unknown “arithmos” and used an archaic Greek letter similar to “s” for the unknown.

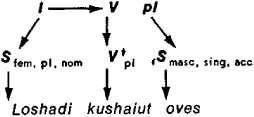

Indian mathematicians made additional algebraic discoveries and developed what are essentially the modern symbols for each of the decimal digits. One especially influential Indian mathematician was Brahmagupta, whose algebraic techniques could handle any quadratic equation. Brahmagupta’s name for the unknown variable was yavattavat. When additional variables were required, he instead used the initial syllable of color names, like “ka” from kalaka (black), “ni” from nilaka (blue) and so on.

Islamic scholars translated and preserved a great deal of both Greek and Indian scholarship that has contributed immensely to the world’s mathematical, scientific and technical knowledge. The most famous Islamic mathematician was al-Khowarizmi, whose foundational text, The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing, is at the root of the modern word “algebra.” (Its Arabic name is abbreviated as “al-Jabr.”)

So, what about “x”?

One theory of the genesis of “x” as the unknown in modern algebra points to these Islamic roots. The theory contends that the Arabic word used for the quantity being sought was al-shayun, meaning “something,” which was shortened to the symbol for its first “sh” sound. When Spanish scholars translated the Arabic mathematical treatises, they lacked a letter for the “sh” sound and instead chose the “k” sound. They represented this sound by the Greek letter “χ,” which later became the Latin “x.”

It’s not unusual for a mathematical expression to come about through convoluted translations. The trigonometric word “sine” started as a Hindu word for a half-chord but, through a series of translations, ended up coming from the Latin word sinus, meaning bay. Still, some evidence casts doubt upon the theory that using “x” as an unknown is an artifact of Spanish translation.

The Spanish alphabet includes the letter “x,” and early Catalan involved several pronunciations of it depending on context, including a pronunciation akin to the modern “sh.” Though the sound’s pronunciation changed over time, there are still vestiges of the “sh” sound for “x” in Portuguese, as well as in Mexican Spanish and native place names. By this reasoning, Spanish translators conceivably could have used “x” without needing to resort first to the Greek “χ” and then to the Latin “x”.