Isaac Newton Thought the Great Pyramid Held the Key to the Apocalypse

Papers sold by Sotheby’s document the British scientist’s research into the ancient Egyptians and the Bible

published : 08 April 2024

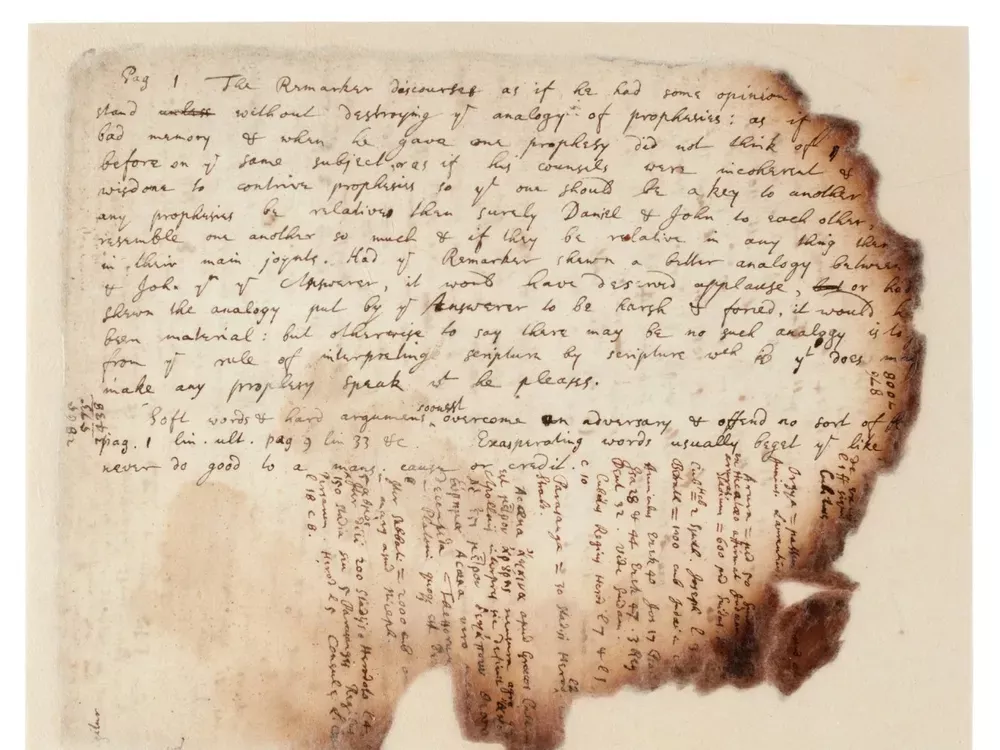

Messages about a coming apocalypse that could be decoded through architectural measurements? Keys to secrets of the Bible found in Egypt’s Great Pyramid? These might seem like nonsensical notions far from the world of science. But for Isaac Newton, they were veritable obsessions detailed in three pages of notes sold by Sotheby’s this morning for £378,000 (around $504,700 USD).

“He was trying to find proof for his theory of gravitation, but in addition the ancient Egyptians were thought to have held the secrets of alchemy that have since been lost,” Gabriel Heaton, Sotheby’s manuscript specialist, tells the Observer’s Harriet Sherwood. “Today, these seem disparate areas of study–but they didn’t seem that way to Newton in the 17th century.”

As Peter Dockrill reports for Science Alert, many of Newton’s unpublished notes concerning alchemy, occult matters and the biblical apocalypse only resurfaced after his death in 1727. In the British scientist’s own day, church leaders would have viewed many of his ideas on these subjects as heretical.

“His descendants made sure very few saw the papers because they were a treasure trove of dirt on the man,” Sarah Dry, author of The Newton Papers: The Strange and True Odyssey of Isaac Newton’s Manuscripts, told Wired in 2014. “… His papers were bursting with evidence for just how heretical his views were.”

Newton was arguably the most significant figure of the 16th- and 17th-century Scientific Revolution. He formulated the three laws of motion that form the basis of modern physics, discovered that white light is composed out of light from different colors and helped develop calculus, among many other accomplishments.

Per the Observer, Newton began studying the pyramids in the 1680s. At the time, he was in self-imposed exile at his family home, Woolsthorpe Manor in Lincolnshire, recovering from an attack on his work by Robert Hooke, a scientific rival and fellow member of the early scientific institution the Royal Society. The notes are burned around their edges—damage attributed to Newton’s dog, Diamond, knocking over a table and toppling a candle.

Like some other European scholars of his day, Newton believed that the ancient Egyptians possessed knowledge that had been lost in the intervening centuries.

“The searching out of ancient occult secrets was a central trope of alchemy, a subject which Newton studied deeply,” says Sotheby’s in the auction listing.

Newton was interested in the cubit, a unit of measurement used by the Great Pyramid’s builders. He believed that it could enable him to figure out the exact dimensions of other ancient structures. In particular, he hoped to learn the dimensions of the Temple of Solomon, which he thought could hold the key to understanding the biblical apocalypse.

The pioneering scientist also tied his interest in the pyramid to his efforts to understand gravity. He thought that the ancient Greeks had successfully measured Earth’s circumference using a unit called the stade, which he believed was borrowed from the Egyptians. By translating the ancient measurement, Newton hoped to validate his own theory of gravity.

Though his discoveries have influenced the course of scientific advancement for centuries, Sotheby’s notes that “to Newton himself they were secondary to his ‘greater’ studies in alchemy and theology. It was the latter that was the greatest motivation for his research on ancient metrology.”

Newton held religious beliefs that were at odds with mainstream Christianity, dismissing the Holy Trinity and instead viewing Jesus Christ as an intermediary between God and humanity. He was also interested in biblical prophecy and hoped to decode its clues to reveal insights on events of the future, particularly the Second Coming.

“These are really fascinating papers because in them you can see Newton trying to work out the secrets of the pyramids,” Heaton tells the Observer. “It’s a wonderful confluence of bringing together Newton and these great objects from classical antiquity which have fascinated people for thousands of years. The papers take you remarkably quickly straight to the heart of a number of the deepest questions Newton was investigating.”