What Online Inflation Calculators Can—and Can’t—Tell Us About the Past

Most of these tools are based on the Consumer Price Index, a measure of changing prices in the U.S. over time

published : 08 April 2024

Economist Joe Mahon lives near a historic restaurant opened by the fast-food operator White Castle in 1936. Though the Minneapolis building is now home to a music nonprofit, it still bears an old White Castle sign proudly touting the chain’s signature 5-cent hamburgers.

One day, a friend casually mentioned to Mahon that he couldn’t imagine paying 5 cents for a hamburger in the modern era—and the wheels in Mahon’s brain started turning. “I suggested it was possible that after adjusting for inflation, a burger now could actually be cheaper,” says Mahon.

Given his role as regional outreach director at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Mahon’s response makes sense. Like any good economist, he decided to crunch the numbers for himself to see if he was right. First, he looked up when a White Castle burger would have cost 5 cents, and landed on the year 1929. Then, he turned to the Minneapolis Fed’s online inflation calculator to see what the price would be in 2022 dollars and got a value of $0.85. “I’m very ashamed to admit I did this in my free time,” he says with a laugh.

Mahon isn’t alone in his curiosity about how the purchasing power of the United States dollar has changed over time. With record-breaking inflation making headlines in 2022, many Americans are thinking more about the economic concept these days—and, as their grocery, rent and gas bills continue to creep upward, they’re turning to online inflation calculators to help make sense of it all. But how accurate and sophisticated are these tools? Can they really help contextualize the changing value of the dollar? And are they useful for understanding the past?

Defining inflation

Inflation measures the overall rise in prices of goods and services, which, in turn, reduces the purchasing power of a currency like the U.S. dollar. Prices can go up—and buying power can go down—for many reasons, including supply shortages and rising consumer demand. An increase in the supply of money (which occurs when governments print more banknotes, like Germany’s Weimar Republic did to pay for the costs of World War I) can also cause hyperinflation, or out-of-control, runaway price increases.

Most online inflation calculators use data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) Consumer Price Index (CPI), which has tracked price changes in the U.S. since 1913. More specifically, CPI measures the prices that urban consumers pay for a “market basket” of common items, like fruits and vegetables, as well as services such as haircuts and doctor’s visits.

As prices go up, the buying power of the dollar goes down, with people unable to buy as much with the same amount of money—a trend that also makes CPI useful for evaluating wages and salaries. Employees might ask for a raise because inflation has eroded the purchasing power of their paychecks, for instance. Though CPI has received its fair share of criticism and been questioned for its accuracy (economists have argued that CPI’s methodology both overstates and understates inflation), for now, it’s the best metric the government has. Online inflation calculators, then, are only as good as CPI. “They’re as accurate as we can make them,” says Mahon.

Online inflation calculators become less reliable when used to compute the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar before 1913. For pre-1913 inflation, calculators have to rely on estimates that economists have retroactively pieced together from advertisements, newspapers and other historical records to get a rough indication of price changes. “We’re confident in data going back to 1913. Before that, it becomes a little sketchier,” says Art Rolnick, the former director of research at the Minneapolis Fed and an economist at the University of Minnesota.

Comparing prices also gets fuzzy when it comes to products and services that have improved over time, such as TVs, cars and smartphones. Though BLS economists do their best to factor quality improvements into CPI (as well as decreases in quantity and product sizes, a phenomenon that’s been called “shrinkflation”), some outside experts argue that they’re not fully capturing these hidden price changes.

“A car today is not the same as a car back in 1950,” says Rolnick. “When we try to compare what we were buying in the basket of goods today to what we were buying years ago, we have to take quality into account and that’s not easy. When you get deep into it, these aren’t easy comparisons.”

Beyond that, most inflation calculators aren’t equipped to explain what’s really going on behind the numbers. Gas is more expensive right now, for example, primarily because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which prompted some Western countries to stop importing Russian oil and gas as part of broader economic sanctions. Labor shortages, supply chain issues and strong consumer spending linked to the Covid-19 pandemic are also to blame for rising inflation. While prices are, on average, increasing, some products are actually cheaper now than they were in the past because of manufacturing innovations, technological advancements and greater competition.

“Inflation is just one number, and prices can go up or down for lots of reasons,” says Rolnick. “What we usually want to know is: Are we better off today than we were yesterday? Is it more expensive or less expensive to buy apples today? Or, just generally, can we buy more goods today than we did previously? And clearly, our standard of living is way up.”

What inflation calculators tell us

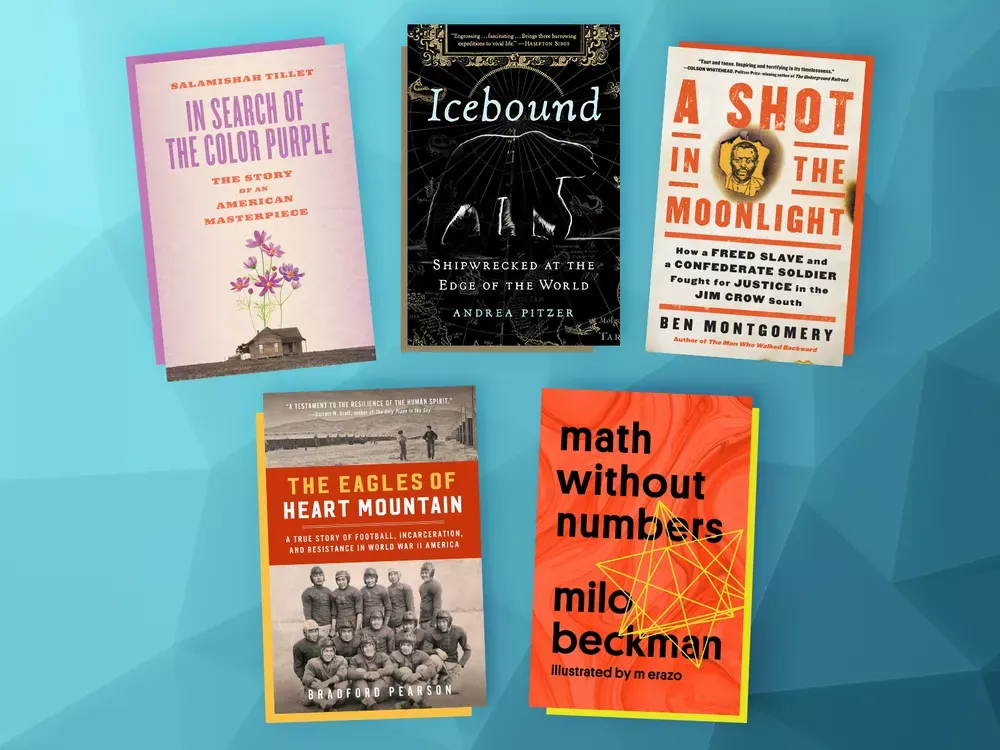

Ian Webster, a 32-year-old software engineer based in San Mateo, California, is also trying to help everyday people better understand the economy with his popular online inflation calculator, which he launched in 2013. His calculator spits out numerical values—for example, $100 in 1913 is worth $2,993.04 today—but it also offers up a wealth of other information, such as the rate of inflation by spending category, the formulas the calculator used and links to data sources. His pre-1913 U.S. data goes back to 1635 and comes from historical studies; he also has data from other countries, including Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia.

“I’d like to think I’m breaking it down in a way that someone can actually walk away with a deeper understanding of what inflation is and how, as an economic concept, it relates to their lives,” Webster says. “There’s one way you can use it, which is to punch in a number and walk away with a number in the headline. But it’s a little tricky to present inflation as a one-size-fits-all number, because it really depends on your spending habits. Everyone’s basket of goods is a little bit different.”

To illustrate how people experience inflation differently depending on their socioeconomic status, purchasing decisions and other factors, the New York Times’ Ben Casselman and Ella Koeze created a somewhat nontraditional “What’s Your Rate of Inflation?” calculator in May 2022. By answering seven simple questions about their spending, travel and eating habits, users can approximate their own personal inflation rate, which helps add more nuance to the numbers in the headlines. Prices began increasing rapidly during the second half of 2021, climbing 6.8 percent year-over-year in November 2021. Then, in 2022, inflation continued its rapid rise, hitting 9.1 percent in June—the fastest pace since November 1981.