The Defiance of Florence Nightingale

Scholars are finding there’s much more to the “lady with the lamp” than her famous exploits as a nurse in the Crimean War

published : 05 April 2024

She’s the “avenging angel,” the “ministering angel,” the “lady with the lamp”—the brave woman whose name would become synonymous with selflessness and compassion. Yet as Britain prepares to celebrate Florence Nightingale’s 200th birthday on May 12—with a wreath-laying at Waterloo Place, a special version of the annual Procession of the Lamp at Westminster Abbey, a two-day conference on nursing and global health sponsored by the Florence Nightingale Foundation, and tours of her summer home in Derbyshire—scholars are debating her reputation and accomplishments.

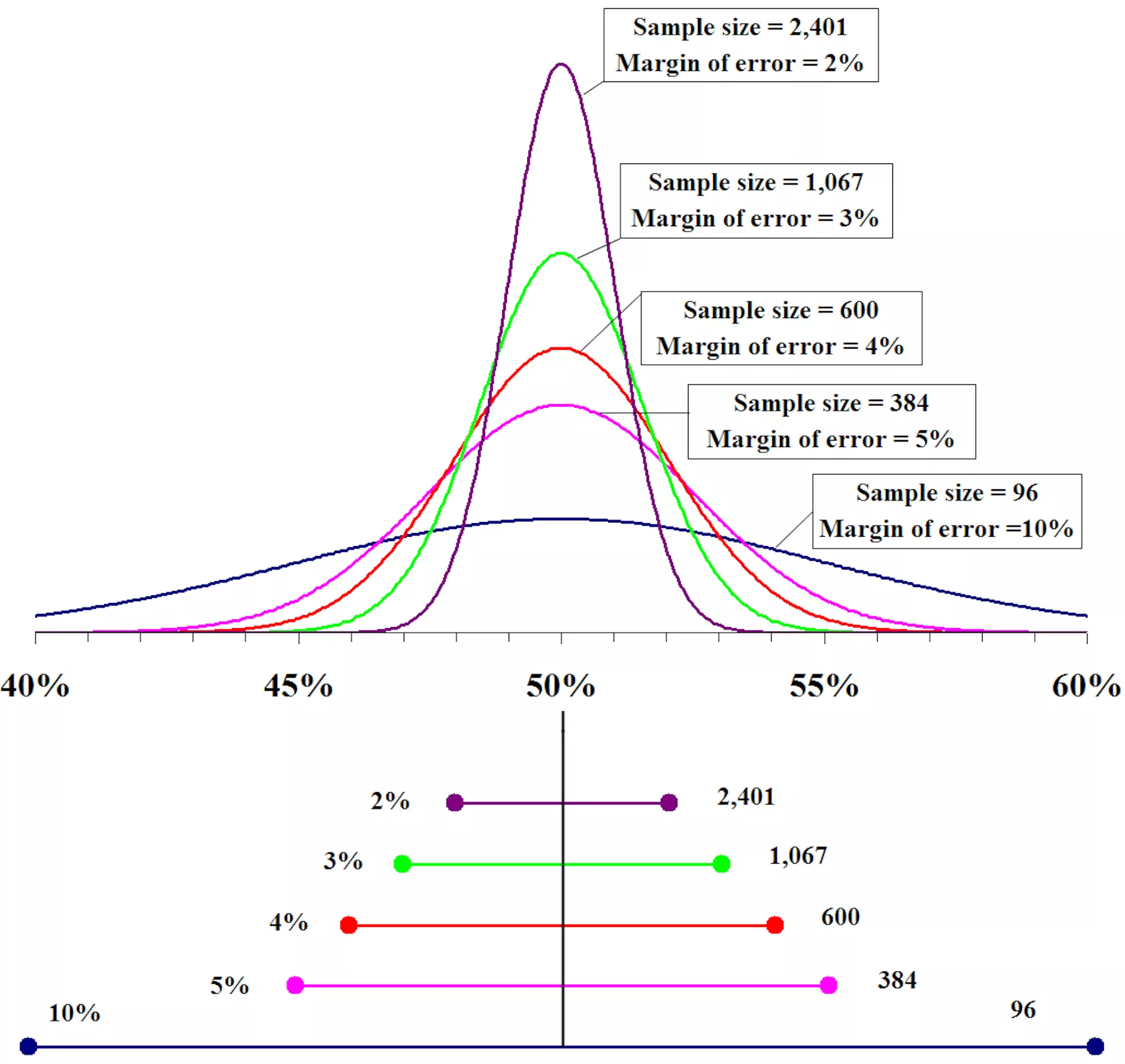

Detractors recently have chipped away at Nightingale’s role as a caregiver, pointing out that she served as a nurse for only three years. Meanwhile, perhaps surprisingly, some British nurses themselves have suggested they are tired of working in her shadow. But researchers are calling attention to her pioneering work as a statistician and as an early advocate for the modern idea that health care is a human right. Mark Bostridge, author of the biography Florence Nightingale, attributes much of the controversy to Nightingale’s defiance of Victorian conventions. “We are very uncomfortable still with an intellectually powerful woman whose primary aim has nothing to do with men or family,” Bostridge told me. “I think misogyny has a lot to do with it.”

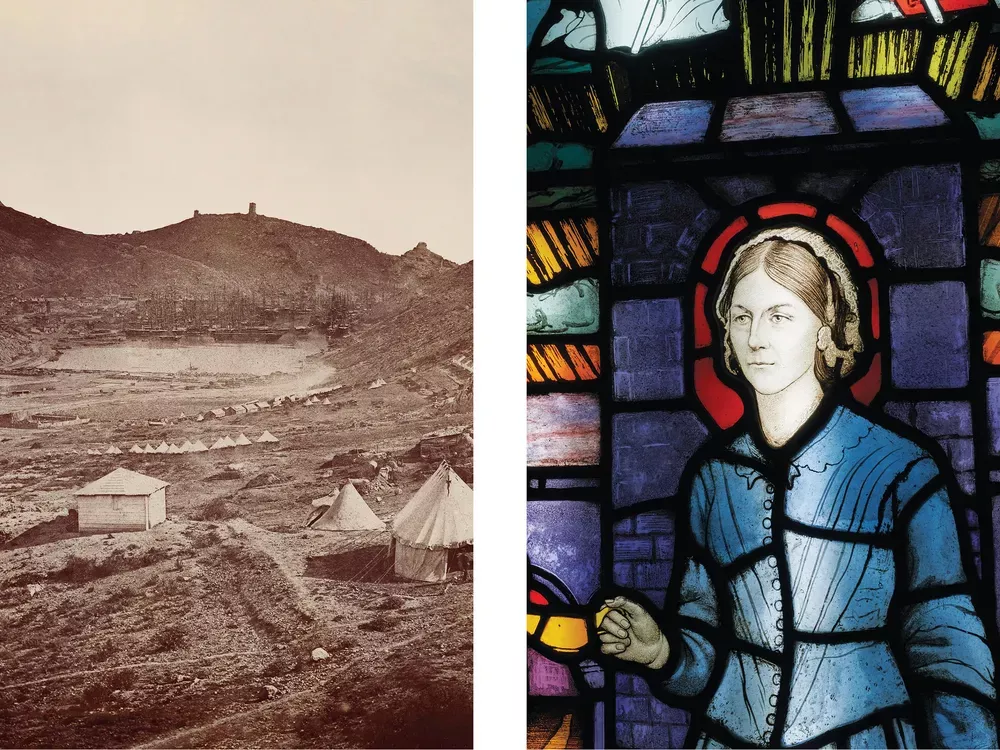

To better understand this epic figure, I not only interviewed scholars and searched the archives but went to the place where the crucible of war transformed Nightingale into perhaps the most celebrated woman of her time: Balaklava, a port on the Crimean Peninsula, where a former Russian military officer named Aleksandr Kuts, who served as my guide, summed up Nightingale as we stood on the cliff near the site of the hospital where she toiled. “Florence was a big personality,” he said. “The British officers didn’t want her here, but she was a very insistent lady, and she established her authority. Nobody could stand in her way.”

She was named in honor of the Italian city where she was born on May 12, 1820. Her parents had gone there after being married. Her father, William Nightingale, had inherited at age 21 a family fortune amassed from lead smelting and cotton spinning, and lived as a country squire in a manor house called Lea Hurst in Derbyshire, set on 1,300 acres about 140 miles north of London. Tutored by their father in mathematics and the classics, and surrounded by a circle of enlightened aristocrats who campaigned for outlawing the slave trade and other reforms, Florence and her older sister, Parthenope, grew up amid intellectual ferment. But while her sister followed their mother’s example, embracing Victorian convention and domestic life, Florence had greater ambitions.

She “craved for some regular occupation, for something worth doing instead of frittering away time on useless trifles,” she once recalled. At 16, she experienced a religious awakening while at the family’s second home, at Embley Park, in Hampshire, and, convinced that her destiny was to do God’s work, she decided to become a nurse. Her parents—especially her mother—opposed the choice, since nursing in those days was regarded as disreputable, suitable only for lower-class women. Nightingale overcame her parents’ objections. “Both sisters were trapped in a gilded cage growing up,” says Bostridge, “but only Florence broke out of it.”

For years, she divided her time between the comforts of rural England and rigorous training and caregiving. She traveled widely in continental Europe, mastering her profession at the highly regarded Kaiserswerth nursing school in Germany. She served as superintendent of the Institution for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen on Upper Harley Street in London, a hospital for governesses. And she cared for prostitutes during a cholera epidemic in 1853.

In 1854, British troops invaded the Russian-held Crimean Peninsula in response to aggressive moves by Czar Nicholas I to expand his territory. With the Ottoman and French armies, the British military laid siege to Sevastopol, headquarters of the Russian fleet. Sidney Herbert, the secretary of state for war and a friend of the Nightingales, dispatched Florence to the Barrack Hospital at Scutari, outside Constantinople, where thousands of wounded and sick British troops had ended up, after being transported across the Black Sea aboard filthy ships. Now with 38 nurses under her command, she ministered to troops packed in squalid wards, many of them wracked by frostbite, gangrene, dysentery and cholera. The work would be later romanticized in The Mission of Mercy: Florence Nightingale receiving the wounded at Scutari, a large canvas painted by Jerry Barrett in 1857 that today hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London. (Barrett found Nightingale to be an impatient subject. Their first encounter, reported one of Barrett’s traveling companions, “was a trying one and left a painful impression. She received us just as a merchant would have during business hours.”)